Articles

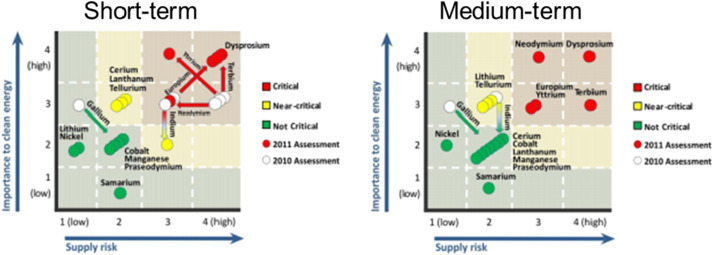

As the technologies we use as a society have advanced, so have the materials used in these technologies. Some of these materials are exotic and highly specialized, making them particularly vulnerable to supply disruptions and supply disruptions particularly impactful. Such materials are designated as “critical” materials. Their level of criticality can be identified by accounting for a number of factors related to their supply risk and the extent to which a supply disruption would impact business operations or society at large. We highlight current methodologies used to assess materials criticality, how these assessments are used to reduce materials-related risk and to what extent there is room for improvement. Particularly, this paper reviews critical materials designations from the United States Department of Energy, the European Union, and the General Electric Company, and how they have changed over the period from 2008 to 2014. The changes suggest that the factors considered in criticality ratings have different natural time scales, and that criticality changes occur both due to supply-side risk mitigation as well as demand-side responses. Response options, whether on the supply or demand side, also span a range of time scales and the interaction between factors with different time scales can play a significant role in the dynamics. To date, many published analyses are snapshots in time. A detailed understanding of how risk profiles evolve remains an open question. The importance and impact of demand-side responses such as recycling, substitution and new technological development are discussed.

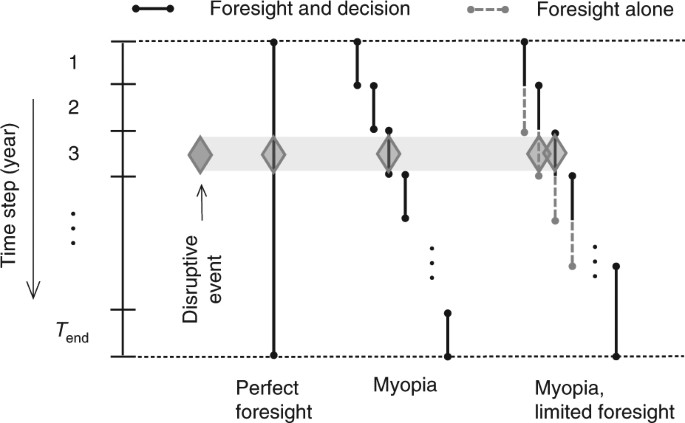

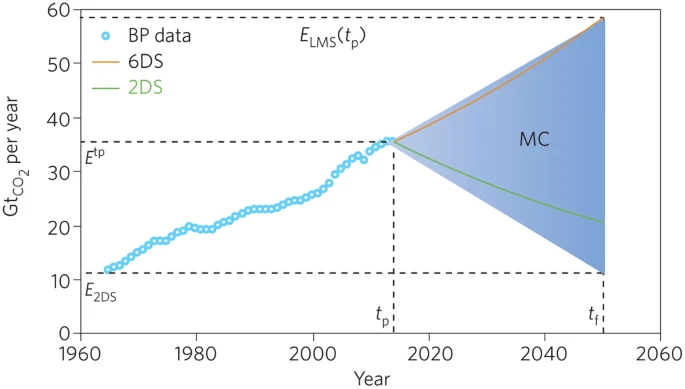

The journey to carbon neutrality will require trillions of dollars of capital investment over many years. Analytical models based on foresight offer guidance, but an overreliance on them can lead to a myopic focus on a single pathway. Some argue that the solution is to develop higher-resolution models, fed with increasingly granular data. Here, we note that real-time feedback is an important and underappreciated complement to this approach.

The delayed deployment of low-carbon energy technologies is impeding energy system decarbonization. The continuing debate about the cost-competitiveness of low-carbon technologies has led to a strategy of waiting for a ‘unicorn technology’ to appear. Here, we show that myopic strategies that rely on the eventual manifestation of a unicorn technology result in either an oversized and underutilized power system when decarbonization objectives are achieved, or one that is far from being decarbonized, even if the unicorn technology becomes available. Under perfect foresight, disruptive technology innovation can reduce total system cost by 13%. However, a strategy of waiting for a unicorn technology that never appears could result in 61% higher cumulative total system cost by mid-century compared to deploying currently available low-carbon technologies early on.

Increasingly, near-100% intermittent renewable scenarios are proposed as viable power system solutions. Underlying assumptions and real-world implications often remain unexplained and unaccounted for. We investigate the effect of such scenarios on security of power supply and find that 100% intermittent renewable power systems could be unable to meet basic peak demand and ancillary services requirements, proving inoperable under current system regulations. Openness and transparency is key, but modelers and model users must also interpret and communicate results carefully to not misguide public opinion and decision makers.

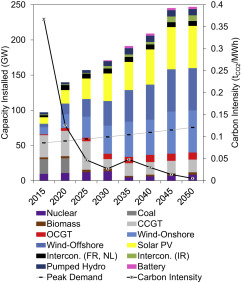

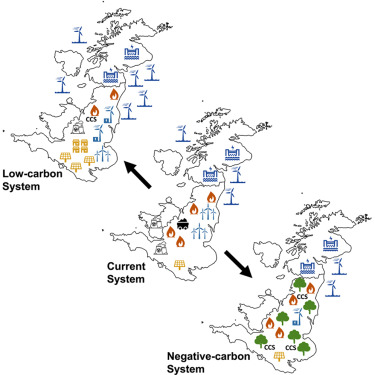

We employ an electricity system model to determine the least-cost transition necessary to meet a given carbon dioxide removal (CDR) burden in the UK. The results show that, while sufficient in the medium term, a system dominated by intermittent renewable energy technologies (IRES) cannot deliver CDR at the scale required in a cost-effective manner. The marginal value of IRES for climate change mitigation diminishes with time, especially in the context of the Paris Agreement. Deeper decarbonization precipitates a resurgence of thermal generation from bioenergy and gas (with carbon capture and storage) and nuclear. Such a system is inherently centralized and will require maintenance of existing transmission and distribution infrastructure. Current policy direction, however, encourages the proliferation of renewables and decentralization of energy services. To avoid locking the power system into a future where it cannot meet climate change mitigation ambitions, policy must recognize and adequately incentivize the new technologies (CCS) and services (CDR) necessary.

Many studies have quantified the cost of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) power plants, but relatively few discuss or appreciate the unique value this technology provides to the electricity system. CCS is routinely identified as a key factor in least-cost transitions to a low-carbon electricity system in 2050, one with significant value by providing dispatchable and low-carbon electricity. This paper investigates production, demand and stability characteristics of the current and future electricity system. We analyse the Carbon Intensity (CI) of electricity systems composed of unabated thermal (coal and gas), abated (CCS), and wind power plants for different levels of wind availability with a view to quantifying the value to the system of different generation mixes. As a thought experiment we consider the supply side of a UK-sized electricity system and compare the effect of combining wind and CCS capacity with unabated thermal power plants. The resulting capacity mix, system cost and CI are used to highlight the importance of differentiating between intermittent and firm low-carbon power generators. We observe that, in the absence of energy storage or demand side management, the deployment of intermittent renewable capacity cannot significantly displace unabated thermal power, and consequently can achieve only moderate reductions in overall CI. A system deploying sufficient wind capacity to meet peak demand can reduce CI from 0.78 tCO2/MWh, a level according to unabated fossil power generation, to 0.38 tCO2/MWh. The deployment of CCS power plants displaces unabated thermal plants, and whilst it is more costly than unabated thermal plus wind, this system can achieve an overall CI of 0.1 tCO2/MWh. The need to evaluate CCS using a systemic perspective in order to appreciate its unique value is a core conclusion of this study.

Negative emissions technologies (NETs) in general and bioenergy with CO2 capture and storage (BECCS) in particular are commonly regarded as vital yet controversial to meeting our climate goals. In this contribution we present a whole-systems analysis of the BECCS value chain associated with cultivation, harvesting, transport and conversion in dedicated biomass power stations in conjunction with CCS, of a range of biomass resources – both dedicated energy crops (miscanthus, switchgrass, short rotation coppice willow), and agricultural residues (wheat straw). We explicitly consider the implications of sourcing the biomass from different regions, climates and land types. The water, carbon and energy footprints of each value chain were calculated, and their impact on the overall system water, carbon and power efficiencies was evaluated. An extensive literature review was performed and a statistical analysis of the available data is presented. In order to describe the dynamic greenhouse gas balance of such a system, a yearly accounting of the emissions was performed over the lifetime of a BECCS facility, and the carbon “breakeven time” and lifetime net CO2 removal from the atmosphere were determined. The effects of direct and indirect land use change were included, and were found to be a key determinant of the viability of a BECCS project. Overall we conclude that, depending on the conditions of its deployment, BECCS could lead to both carbon positive and negative results. The total quantity of CO2 removed from the atmosphere over the project lifetime and the carbon breakeven time were observed to be highly case specific. This has profound implications for the policy frameworks required to incentivise and regulate the widespread deployment of BECCS technology. The results of a sensitivity analysis on the model combined with the investigation of alternate supply chain scenarios elucidated key levers to improve the sustainability of BECCS: (1) measuring and limiting the impacts of direct and indirect land use change, (2) using carbon neutral power and organic fertilizer, (3) minimising biomass transport, and prioritising sea over road transport, (4) maximising the use of carbon negative fuels, and (5) exploiting alternative biomass processing options, e.g., natural drying or torrefaction. A key conclusion is that, regardless of the biomass and region studied, the sustainability of BECCS relies heavily on intelligent management of the supply chain.

To offset the cost associated with CO2 capture and storage (CCS), there is growing interest in finding commercially viable end-use opportunities for the captured CO2 . In this Perspective, we discuss the potential contribution of carbon capture and utilization (CCU). Owing to the scale and rate of CO2 production compared to that of utilization allowing long-term sequestration, it is highly improbable the chemical conversion of CO2 will account for more than 1% of the mitigation challenge, and even a scaled-up enhanced oil recovery (EOR)-CCS industry will likely only account for 4–8%. Therefore, whilst CO2-EOR may be an important economic incentive for some early CCS projects, CCU may prove to be a costly distraction, financially and politically, from the real task of mitigation.